The feast of the dead and its rites: from Celtic to Cremonese peasant tradition

The feast of the dead and its rites: from Celtic to Cremonese peasant tradition

by Hasan Andrea Abou Saida

The origin of the festivities and rituals of the Cremonese rural world can be found in the customs and traditions of the ancient peoples who lived here thousands of years ago. Long before the conquest and creation of the Roman colony in 218 B.C., in the area where Cremona now stands lived the Celts, an Indo-European population coming from Asia Minor and arriving in Europe around 3500 B.C.. The Celts were composed of many tribes, and some of them, called Insubri, settled in the Po Valley between the 5th and 4th centuries BC. But before the Celts, this area was inhabited by another population, the Ligurians, the true Italic natives. Very little remains of the Ligurian presence in Padania, especially the linguistic fragments. The suffix ‘ona’ in fact gives us confirmation of the actual settlement of Ligurians in the Cremona area. Suffixes are usually those ending in ‘asco’, Livrasco, Porcellasco, Marasco. It is not difficult to think that these two peoples exchanged knowledge, giving rise to a common tradition of rites and celebrations. The spirituality of our ancestors, both Celts and Ligurians, was based on the cycles of Nature, the alternation of the seasons and the movements and influences of the heavens. Ancient man lived in close symbiosis with Mother Nature on whom he depended, and on whom he still unconsciously depends today. In this article, we will try to rediscover the ancient Celtic roots of Cremonese traditions, in order to better understand the deep meanings of certain festivities and rituals still present in our life and society.

Feast of the Dead and Saints – 31 October / 1 – 2 November

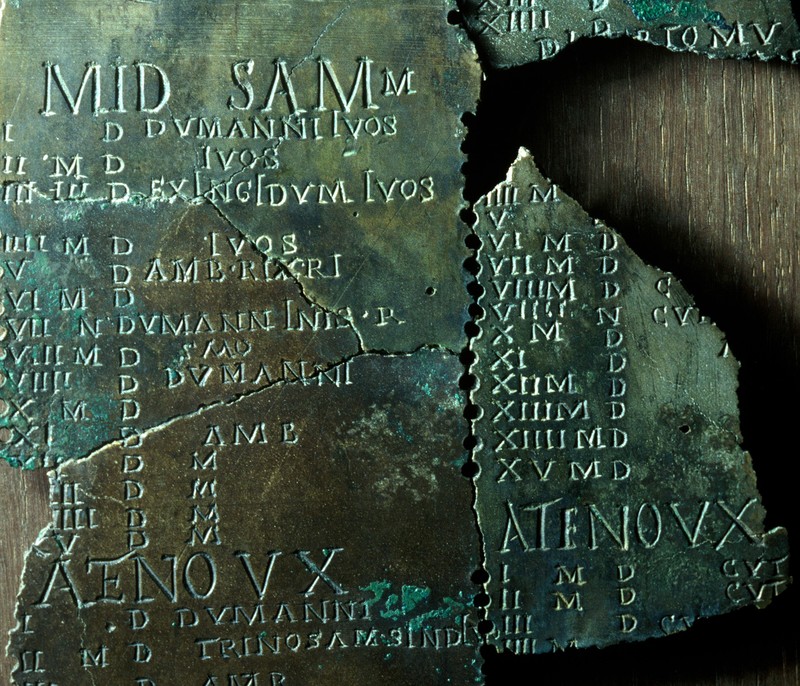

According to the Celts, the year was divided into two equal parts and began on 1 November with the feast of Samhain or Samonios (as it was called by the Insubri Celts), the “dark” half of the year; Samhain reached its climax on 1 May with the feast of Beltane or Cetsamltain, the beginning of the “light” half. The Celts, through these two particular times of the year, celebrated the rising and setting of the Pleiades, a group of stars in the constellation Taurus which were very important to many peoples, thus indicating the two fundamental points in the wheel of the year.

Samonios, or the “Time of the End of Summer”, marked the end of the old year and the beginning of the new one: a symbol of death and rebirth, it was considered an open door between two dimensions, the earthly and the spiritual. At this time, the season of green ends and that of the seed begins. It is time to gather the last fruits, the time of the last harvest, to sustain us throughout the winter. As the first winter colds approached, the herds and flocks were gathered in Samonios and all the animals were slaughtered, except for those destined to breed the following season. These days were marked by a great consumption of food that satisfied everyone for the last time before the hardships of winter, and therefore included the consumption of excess food that could not be stored. The culmination of this festivity occurred on the eve of 31 October, when the dark half of the year was entered and the gates of the Underworld were opened to connect the spiritual and the earthly worlds 1.

According to the Celts, the year was divided into two equal parts and began on 1 November with the feast of Samhain or Samonios (as it was called by the Insubri Celts), the “dark” half of the year; Samhain reached its climax on 1 May with the feast of Beltane or Cetsamltain, the beginning of the “light” half. The Celts, through these two particular times of the year, celebrated the rising and setting of the Pleiades, a group of stars in the constellation Taurus which were very important to many peoples, thus indicating the two fundamental points in the wheel of the year.

Celtic festivals always began a week before the day indicated and continued for another week, for a total period of 15 days. The Samhain celebrations ended on 11 November, the day which in Christian tradition coincides with the summer of St Martin. During this period, spirits of ancestors would return to walk among the living, giving both worlds the opportunity to exchange messages and celebrate together. Samhain is the point of conjunction between two years (the old and the new) and between two worlds (the visible and the invisible), belonging neither to the previous nor to the following one, a day out of time and space.

For this reason, Samonios was the most suitable time to practise divinatory rites concerning the prediction of the weather, marriages and good fortune for the coming year. It was also the time for important meetings, battles and ritual sacrifices. During the night, all the fires in each village were extinguished, only to be rekindled with a New Fire the following morning 2.

In English-speaking countries, Samhain’s eve, 31 October, has thus taken the name All Hallows’ Eve, more popularly known as Halloween night, during which people go around disguised as monsters, witches and goblins. The modern masquerade, however, echoes the ancient practice of ritual initiatory disguise used by ancient European shamans to connect with spiritual reality, ancestors, benign spirits and gods, while protecting themselves against evil spirits. All this can be found, modified in the names and adapted to Christian symbolism, in the popular traditions of Cremona. On the morning of 1 November in the 19th century, for example, girls of marriageable age would take wild flowers from their drawers, picked in summer and dried, and use them to create a braid which they would then throw over their shoulders; depending on the shape of the braid, they would try to read a letter of the alphabet, the initial of the man they were to marry 3.

For our Celtic ancestors, the feast of Samhain also turned into a great banquet attended by both the living and the dead, full of pork, wine, beer and mead.

Similarly, in some parts of the Cremona area the tables were not cleared, so that the dead could also eat. A variation of this rite was to prepare as many places on the table as there had been dead people in recent times. On the morning of 2 November, the master of the house would get up earlier than usual and get all the family members to make their beds with special care, taking care to fluff the pillows so that the dead, tired from the long journey, could sleep well in their beds. For the same reason, in other houses the beds were not made at all on 2 November, so that the dead could feel more comfortable in the warmth of their families 4.

Another nineteenth-century custom was to spend the night of 1 November in front of the gates of the Cemetery waiting for it to open. Entering the cemetery first on 2 November was considered auspicious, as all the souls of the deceased would be grateful. Some cemeteries, such as that of Soresina, were equipped with benches to make the night more comfortable. The wake was enlivened by bonfires, bottles of wine and roasted chestnuts, a real feast. After opening the cemetery, people went to the graves of their loved ones to light a candle and lay out fields of flowers. The candles lit on 2 November had magical powers, and the remains of the extinguished candle were collected and taken home, forming small candles that acted as protective amulets in the event of major calamities in the family. After leaving the cemetery, the first concern was to go to an inn to drink wine and eat the typical fagiolini dell’occhio con le cotiche, the typical dish of the Day of the Dead (handed down from the Celtic custom of eating pork and wine). Other typical dishes on 2 November were chickpea or broad bean soup, ritual food for the dead. On a symbolic level, the bean, like all legumes and especially broad beans, are linked to chaos and the forces of the underworld (Saturn – Moon). In the countryside, mothers advised their children not to linger in the bean fields, because the devil might appear to them. The runner bean was the only bean species to be found in the diet of the Etruscans and other Italic peoples, confirming its antiquity. For this reason it was eaten on the days of the dead, a magical protective action (the hermetic principle of “like cures like”), just like ritual disguises.

For the same reason, the characteristic dessert of this period, the ossi dei morti, bone-shaped biscuits as hard as a bone, and roast chestnuts were consumed. Another tradition in Cremona was to consume spirits after hearing the First Mass and before going to the cemetery: people would go to an inn and take a small glass of grappa, a ritual that even children were subjected to (spirits like “spirit”) 5.

Feast of St Martin – 11 November

St Martin’s Day, as we have mentioned, marked the end of the Samonios period and the end of the agricultural year. Today, this function is less evident than it used to be, when in the 19th century in Cremona, this was the day when courts, schools and parliaments began their activities, municipal elections were held, rents and leases were paid, agricultural contracts were renewed or people moved house, so much so that today people still say “far San Martino” for moving house. Peasant families had the opportunity on this day to change farms, find a new job, look for a new home, which was not always easy. Once the new contracts had been signed, the families loaded their belongings onto a farm wagon and set off for a new destination, knowing that in a year’s time they would probably have to move.

It was also a day of festivities with fairs, fires and banquets washed down with new wine, because “for St Martin, every must is wine”. A centuries-old custom in Cremona was to tap the new wine for St Martin, sending some to friends and relatives or inviting them for their first taste. It was a real ceremony conducted by the ‘brentatore’, who wore the classic blue scusalèta with large pockets in front: he would spill a little wine into his wooden bowl, taking a small sip, and confirming the goodness of the wine to his master 6.

Similar to the great Celtic banquets that concluded the Samonios period, in the Cremona area it was customary to feast merrily on St Martin’s Day. Especially in northern Italy, in addition to seasonal products such as wine and roasted chestnuts, pork and goose dishes were eaten on St Martin’s Day. At this time, wild geese migrated (and still do) from north to south, making them easy prey for hunters. The goose is also the symbolic animal of St Martin and reveals, as we shall see, the very close relationship between the legendary figure of the saint and the Celtic tradition. The name Martin derives from the Latin Martinus and means “consecrated to Mars”. Martin of Tours was born in Sabaria Sicca, an outpost of the Roman Empire on the border with Pannonia. His father, a military tribune of the legion, gave him the name Martinus in honour of Mars, the god of war. As the son of a veteran 7.

St Martin’s Day took on the functions of an agricultural and Celtic New Year, more than any other previous festivity. In the early Middle Ages, Martin was the most popular saint in the West, especially in France where more than five hundred towns and villages bear his name. He was the patron saint of the French monarchy, but also of churchgoers, soldiers, travellers who hung a horseshoe on the portal of the church dedicated to him, innkeepers and hoteliers, vintners, grape pickers and many confraternities. St Martin represents a soldier saint riding a white steed with a short cape (cloak) fighting the devil and the evils of the world. Legend has it that St Martin rides through the fields on a white horse, causing the first snow of the season to fall from his cloak 8.

In the province of Bergamo, it is a tradition that on the night between 10 and 11 November, St Martin brings presents to all children, just like on St Lucia’s Day.

The figure of the knight St Martin recalls a Celtic cult of a knight god who also wore a short cape: the cult originated in Pannonia, the Celtic land and home of St Martin. He was a god of the underworld who triumphed over death by passing through a place of a hundred doors, Wigalois the knight with the wheel. But Martin the divine-saint could not reign over the Christian hell, so he was transformed into a knight who fights the devil and rides a white steed 9.

The hellish creature of the knight god of the Celts survived in parts of Southern Ireland until the 19th century in the figure of the hobby horse, known as Láir Bhán (white horse). A man covered in a white sheet and carrying a decorated horse skull (representing the Láir Bhán ) led a group of young people from farm to farm, playing cow horns. At each farm, the youth recited verses, some of which ‘strongly savoured paganism’, and the farmer had to donate food. If the farmer donated food, he could expect good luck from the ‘Muck Olla’; not doing so would bring bad luck 10.

Moreover, St Martin’s Day was the most important fair in Italy for animals with horns, i.e. cows, oxen, bulls, goats and rams. Popular imagination has therefore ironically promoted St Martin as the patron saint of betrayed husbands. Beak hunting’ was a custom similar to scapegoating. According to the mentality of the time, the betrayed husband had been guilty of a serious crime, since his wife’s adultery was considered a sign of the man’s weakness, of his inability to control his wife; and so the ‘beak’ had to undergo a playful ritual persecution. And so the circle closes with the re-enactment of the masquerades that took place at Samonios, wearing the skins and horns of the animals killed for the sacrifice 11.

1 Taraglio, R. (2005). Il vischio e la quercia : la spiritualità celtica nell’Europa druidica (Nuova). Torino: L’età dell’acquario, pagg. 365 – 367.

2 Ibid.

3 Dacquati, L. (1980). Ròbe de na vòolta. Cremona: Edizoni de “Lo Sport Cremonese.”, pag. 171.

4 Ivi, p. 175.

5 Ivi, pp. 173 – 174.

6 Ivi, pp. 181-182

7 Martino di Tours. (28 ottobre 2020). Wikipedia, L’enciclopedia libera, https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martino_di_Tours (last visit 02/11/2020).

8 Cattabiani, A. (1988). Calendario : le feste, i miti, le leggende e i riti dell’anno. Milano: Rusconi CDE, pagg. 213 – 217.

9 Ibid.

10 Samhain. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Samhain&oldid=986093100 (last visit 30/10/2020)

11 Cattabiani, A. (1994). Lunario: dodici mesi di miti, feste, leggende e tradizioni popolari d’Italia. Milano: Mondadori, pag. 341.

Bibliography

Dacquati, L. (1980). Ròbe de na vòolta. Cremona: Edizoni de “Lo Sport Cremonese.”