The Little People and the Fairy Tales

The Little People and the Fairy Tales

by Hasan Andrea Abou Saida

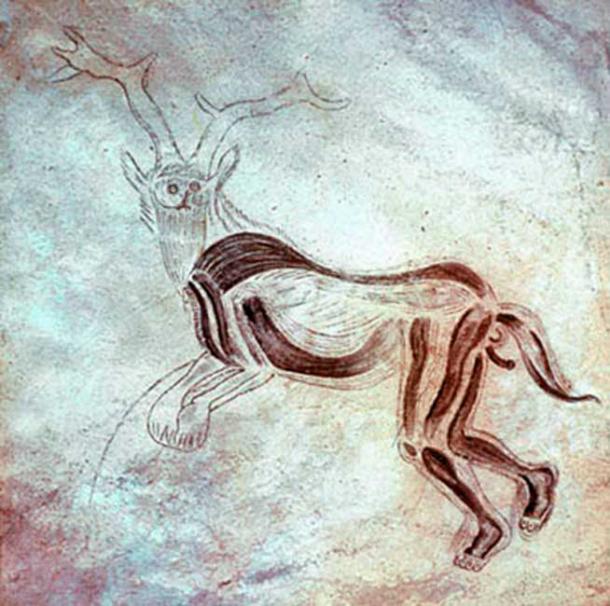

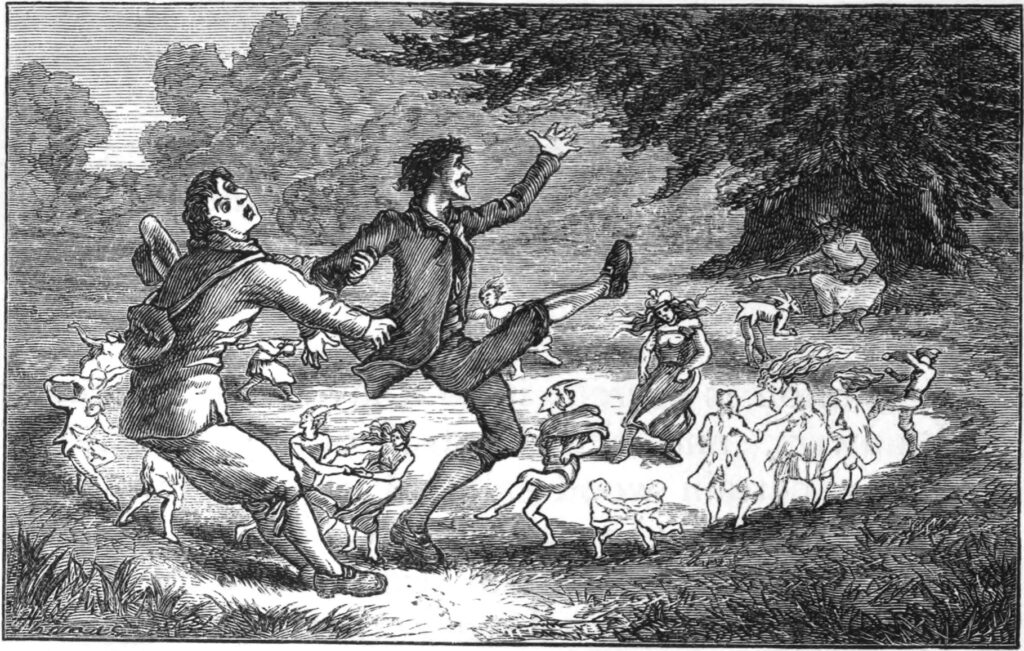

Since the dawn of civilisation, the Spirits of Nature, commonly known by many names such as Little People, Good People, People of the Hills, Woodland Spirits or Sidhe have been the eternal protagonists of tales and fairy tales of magic, folklore and local folk traditions. The term ‘Little People’ refers to the numerous spirits present in the vast realm of Mother Nature, referred to by the most varied names such as elves, gnomes, elves, fairies, sylphs, dragons, ogres, mermaids and many more. Throughout the millennia, man has handed down through writing, art and oral accounts the existence of spirits and the profound relationship between us and these extraordinary beings. This knowledge of and relationship with ancestral spirits is visible and present already in the earliest rock art testimonies from around 40,000 BC. In fact, our ancient ancestors recorded in cave paintings many humanoid figures and therianthropes, otherworldly entities that were recorded together with geometric images, stylised animals and landscapes, and which represent the earliest known folklore in history. This pictorial folklore can be found throughout the Paleolithic world, but the earliest reliably dated rock art can be found at rock sites in Europe, where the oldest evidence is to be found at Fumane, in northern Italy near Verona, and at the Chauvet Caves in the Ardèche region of southern France. In the most famous cave painting complex of Trois Frères in south-western France, there is the cave figure of “The Sorcerer”, a spirit composed of various animals including an owl, a wolf, a deer and a human being.

The Scottish journalist, writer and researcher Graham Hancock, in his book “Shamans”, refers to the studies and research conducted by the South African anthropologist David Lewis-William on many cave paintings around the world, where the latter argues that the depictions were produced by shamanic cultures to represent perceived reality in an altered state of consciousness, thanks also probably to the ritual intake of certain psychotropic compounds such as the famous Amanita Muscaria mushroom. Hancock takes up this interpretation, coming to the conclusion that many magical entities and Nature Spirits described in this era are probably the same as those depicted in cave paintings. Some writers and folklore researchers such as Carlo Ginzburg and Emma Wilby have stated that there is a direct link between shamanic narratives and folklore embodied in classical, medieval and later periods, and often describe entities such as fairies, nymphs, mermaids, elves, etc.

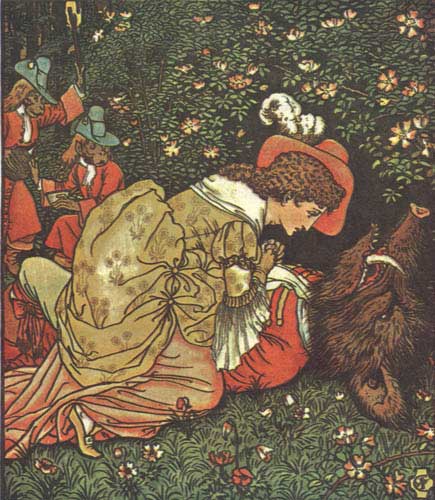

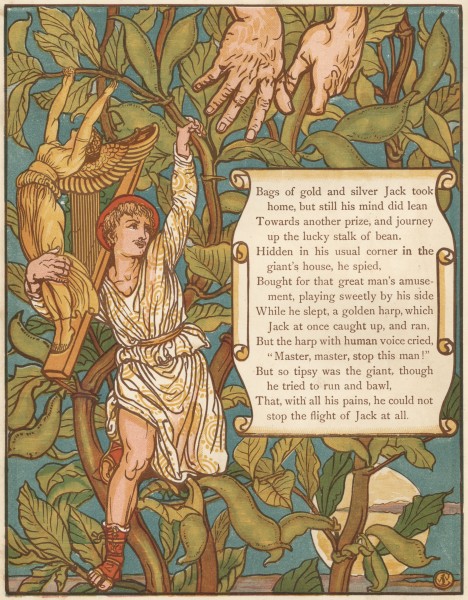

In a study published in the journal Royal Society Open Science in 2016 and conducted by anthropologist Jamie Tehrani of Durham University and researcher Sara Graça da Silva of the New University of Lisbon, using some techniques normally employed by biologists, they analysed the connections between 275 Indo-European magic tales, a category of tales featuring beings and/or objects with supernatural and magical powers, where it was discovered that some tales had prehistoric roots. In fact, researchers discovered that some tales were older than the earliest known literary documents, even dating back to the Bronze Age. For example, the fairy tale “Jack and the Beanstalk”, and its archaic origin story form “The Boy Who Stole the Ogre’s Treasure”, originated when the Eastern and Western Indo-European languages separated, i.e. more than 5,000 years ago. The folk tale “The Blacksmith and the Devil”, where a blacksmith sells his soul in a pact to the devil in order to acquire supernatural abilities, is estimated to date back 6000 years. Even the fairy tales “Beauty and the Beast” and “Rumpelstiltskin”, first written in the 17th and 18th centuries, are actually at least 4000 years old. The study used phylogenetic methods to investigate the relationships between population histories and cultural phenomena such as languages, marriage practices, political institutions, material culture and music. The researchers also used a “tree” of Indo-European languages to trace the lineage of shared narratives, in order to establish how far back in time they went. Dr Tehrani said: “They have been told since before English, French and Italian even existed. They were probably told in an extinct Indo-European language”. She adds that “Some of these stories go back much further than the earliest literary documentation and indeed further than classical mythology – some versions of these stories appear in Latin and Greek texts – but our results suggest that they are much older than that”.

Even Russia’s greatest fairy scholar Vladimir Propp, in his book “The Historical Roots of Fairy Tales” shows how tales and fairy tales of magic, featuring fairies, goblins, elves and other Nature spirits, are the oldest historical documents dating back to Indo-European prehistory. Propp, analysing more than a hundred Russian folk tales from the fairy-tale corpus of Alexander Fyodorovich Afanasyev, establishes how magic tales are closely related to the oldest initiation rites. The hero, as a young initiate, is subjected to numerous trials, which he overcomes by supernatural means or with the help of magical figures, reaching the status of a mature man. All this confirms the existence of these Nature Spirits and a very deep connection between them and the men of Indo-European societies in times past.

Bibliography