Robin Hood, a Green Spirit

Robin Hood, a Green Spirit

by Hasan Andrea Abou Saida

The myth of Robin Hood has been handed down for centuries through stories, legends and popular traditions that depict him as a legendary hero in the service of true justice and in defence of the weakest. But the real historical existence of this character has been questioned on several occasions by many experts: the origins of the myth are in fact very ancient and are lost in history, with no coincidence between the literary – folkloric character and a precise historical figure. In an article published in 2020 in the “National Geographic” historical magazine, the historian J. Rubén Valdés Miyares asserts that the figure of Robin Hood is merely a nickname typical of the outlaws, used at different times and in different places in medieval England 1. Another hypothesis was recently formulated by historians Graham Phillips and Martin Keatman who, after cross-referencing a large amount of historical data with legends, concluded that Robin Hood was a fusion of three distinct characters: a proscribed peasant from Barnsdale Forest who lived around 1225; Robert Hood of Wakefield, a soldier in the rebel army of the Earl of Lancaster, who then entered the service of Edward II in 1324; and Fulk Fitz Warine, one of the barons who rebelled against King John of England between 1200 and 1215 2. Such a thesis, however, does not justify the popularity and success of the archetypal Robin Hood myth, which is most likely based on archaic symbolism and rituals predating the 12th century.

The hero’s name, which reveals his nature, is composed of two different symbolic meanings: the first name Robin was originally the Old French diminutive of the name Robert, which derives from the Old Germanic appellation *Hrōthi- “fame” and *berht- “bright”, meaning “the famous shining one” 3. The second name, Hood, derives from Old English hōd and literally means ‘hood’. It is also possible and probable that the noun “Hood” may be a mispronunciation of “Wood”, as the two nouns have approximately the same pronunciation 4.

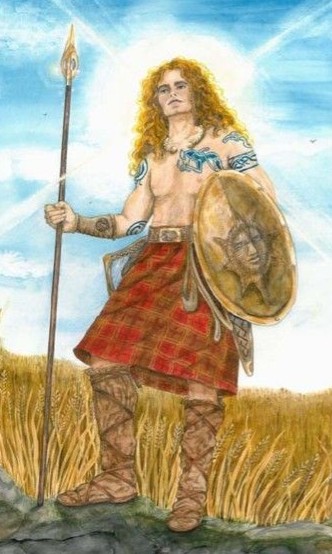

According to many scholars, the origin of the cult of Robin Hood lies in the Celtic world. In particular, a Celtic solar deity with characteristics very similar to Robin Hood is the god Lugh. The Celtic hero is the solar god par excellence in Irish mythology, the incarnation of the Spirit of Grain and king of the mythical Tuatha de Danann. The word Lugh etymologically comes from the Proto-Indo-European root *Leuk “light” (cf. Greek leukós “brightness, whiteness” and Latin lux “light”) 5. Lugh is therefore, like the hero Robin Hood, the Bright One, a god linked to the glow, the warmth of light, but also to a deep sense of justice. In Irish texts, Lugh is presented as both a priestly and military god, but also as the deity of merchants, travellers and thieves. It is no coincidence that the medieval hero Robin Hood and his band also bring justice to the helpless, stealing from the rich to give to the poor and returning to the citizens the huge taxes collected by the Sheriff of Nottingham, his arch-enemy. Both heroes are also connected to the solar symbolism of the Lion: following a comparative mythological line, the Welsh equivalent of the god Lugh is Lleu Llaw Gyffes. His name means ‘Lion with a steady hand’, and was given to him by his own mother when she saw him hit a wren with a sling 6. The lion, with its flaming mane, refers to the sun’s luminous rays and to the principle of solar power at its highest expression. The festival that bears the name of the god Lugh is called Lughnasadh and is celebrated on 1 August, when the harvest and in particular the Spirit of the Grain is celebrated. On the other hand, Robin Hood is also connected to the Lion, as he is a devoted warrior and faithful to the rightful ruler of England, Richard the Lionheart (bearer of the lion archetype).

According to studies by the American professor Juliette Wood, the Proto-Celtic *Lug-u-s can be related to the word *lug-, ‘oak’ 7. Its Gaelic name Duir or Dair, as well as meaning ‘oak’, also means ‘door’, and for a long time the oak was known as the Robust Guardian of the Door. The symbolism of the oak as door or threshold is evident when one associates it with the festival of Lughnasadh, the climax of summer, the festival of the King, the centre of the bright season and the highest expression of lion-solar energy.

Moreover, Robin Hood and his gang were, from the earliest ancient tales, the protagonists of numerous English folk ballads, sung by court jesters and minstrels and preferred by the public to all others. In English villages, the exploits of Robin Hood were sung mainly during the feast of May Day, a celebration marking the beginning of Spring in medieval times 8. As King of May, Robin Hood joined the ‘Lady of the First Day of Spring’, otherwise known as the ‘Lady of May Day’, or Lady Marian. These popular theatrical performances echo the oldest Celtic celebrations of Beltane, a time when life and light manifested themselves in their most triumphant and powerful aspect, a time of fertility where the God of the Forest united with the Great Mother Goddess.

In short, all these elements reveal in the figure of Robin Hood a druidic and divine nature, the archetype of the God/Guardian of the Wood and of Sacred Nature, who encompasses all the knowledge of Nature. According to folklore, together with his merry band of companions, the outlaw hero hid to escape the sheriff and dwelled at the Major Oak, a gigantic thousand-year-old oak tree in Sherwood Forest Royal. The oak is among the most sacred trees for the priestly caste of the Druids, from which the entire Druidic symbolic system is derived. In fact, author Edward Jones says that Derwydd, the Welsh term for the Druids, can be translated as ‘oak body’; Bardd as ‘branches’, or rather the translation of the term derived from bar, ‘summit branch’; Owydd would mean ‘sprout’, but referring to a person would stand for ‘novice’. It is thought that the Druids preferred its shade to that of other trees to meet, dispense their teaching and perform various rituals, and associated the tree with ceremonial order and higher magic 9.

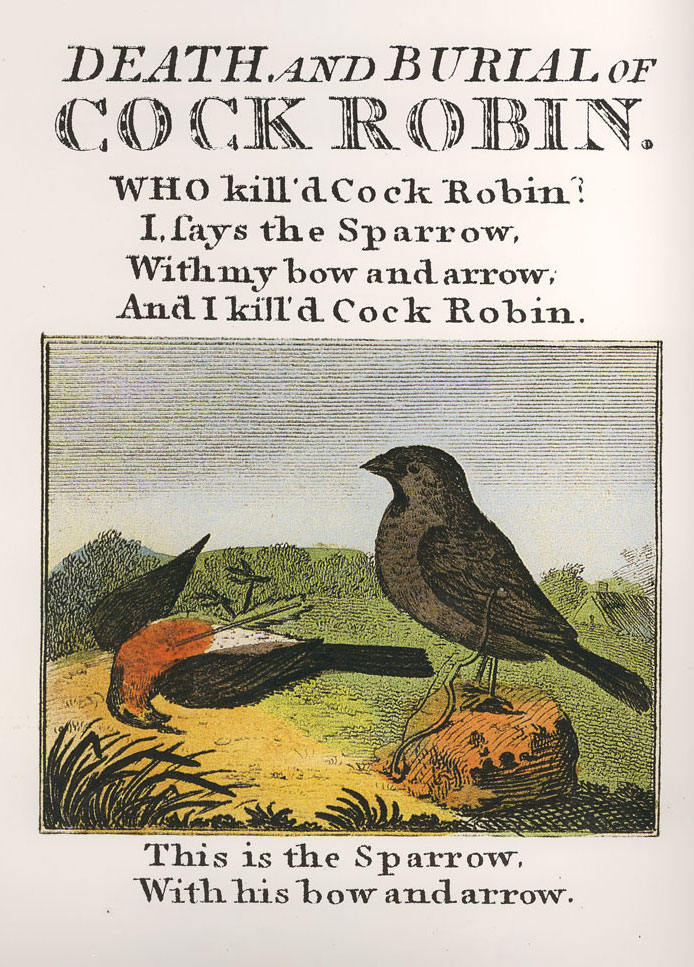

Robin Hood therefore, just like the god Lugh, became the archetype of the warrior-sacred function in medieval folklore. His name is also associated with the robin (in English it is called robin, robin-redbreast or ruddock) and with the cyclical traditions of the year. In a famous nursery rhyme entitled “Who Killed Cock Robin” in 1744, it is told how this bird was killed by a sparrow with an arrow and then buried by all the animals in the wood. The killing of the robin is to be seen as a metaphor for the arrival of spring (the murderous sparrow killing the robin with a bow and arrow) where winter is swept away and all of nature celebrates the ritual of burial and rebirth.

In oral tradition, a variant of this struggle is represented by the robin and the wren, hidden in the leaves of the two respective trees. The wren represents the waning year, the robin the new year and the death of the wren is a death-rebirth transition. Despite its aggressive and not at all shy character, the robin is often associated with calm, peace and tranquillity, but in Celtic tradition, the robin shows off its fighting nature and fights from the branches of a holly tree against a wren placed on an oak tree, symbolising the passage from summer to winter and from the old year to the new one 10. This alternation is similarly represented by the struggle between King Holly (or Mistletoe), representing the rising year, and King Oak, representing the dying year. During the winter solstice, King Holly wins over King Oak, and vice versa for the summer solstice. The two birds are hidden in the two trees so that the wren represents the waning year and the robin the new year 11.

In conclusion, the figure of Robin Hood is a multifaceted and complex legacy of ancient local and Celtic traditions, revealing a solar divine archetype linked to the forces of the annual cycle and Nature.

1 Robin Hood, storia e leggenda di un proscritto, National Geographic, https://www.storicang.it/a/robin-hood-storia-e-leggenda-di-proscritto_14685 (last visit 10/04/2021).

2 Per maggiori approfondimenti vedi: Phillips, G., & Keatman, M. (1996). La leggenda di Robin Hood: sulle tracce dell’eroe fuorilegge e delle sue generose imprese. Casale Monferrato: Piemme.

3 Robert, Online Etymology Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/word/Robert#etymonline_v_15129 (last visit 10/04/2021).

4 Hood, Online Etymology Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/word/hood#etymonline_v_14420 (last visit 10/04/2021).

5 Matasović, Ranko, Etymological dictionary of proto-Celtic, Leiden Indo-European Etymological Dictionary Series 9, Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2009, p. 247.

6 Agrati, G., & Magini, M. L. (1982). Antiche fiabe e leggende celtiche. Milano: Mondadori, pagg. 105 – 106.

7 Lleu Llaw Gyffes. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Lleu_Llaw_Gyffes&oldid=99055676 (last visit 10/04/2021).

8 Robin Hood was so intimately connected to May Day rituals that as early as 1578 the Scottish General Assembly asked the king to ban performances of “Robin Hood, King of May”.

9 Taraglio, R. (2005). Il vischio e la quercia : la spiritualità celtica nell’Europa druidica (Nuova). Torino: L’età dell’acquario, pag. 103.

10 Canzone dello scricciolo, Terre Celtiche Blog, https://terreceltiche.altervista.org/the-wren-song-and-wren-hunting/ (last visit 10/04/2021).

11 Fàél, A. (2020). Un viaggio ad Avalon. Sossano: Anguana Edizioni, pag. 107.

Bibliography

Agrati, G., & Magini, M. L. (1982). Antiche fiabe e leggende celtiche. Milano: Mondadori.

Dumas, A. (1948). Robin Hood. Milano: Lucchi.

Fàél, A. (2020). Un viaggio ad Avalon. Sossano: Anguana Edizioni.

Le ballate di Robin Hood – a cura di Nicoletta Gruppi (1991). Torino: Einaudi.