Saint Andrew, the Winter Gate

Saint Andrew, the Winter Gate

by Hasan Andrea Abou Saida

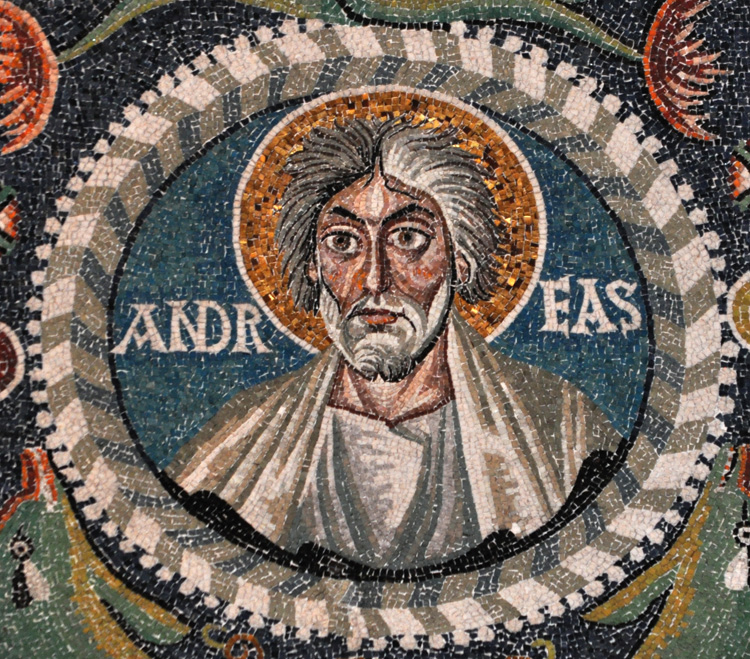

The cult of St Andrew the Apostle is one of the most heartfelt and widespread in Europe. The feast is celebrated on 30 November in the Eastern and Western Churches and in Scotland it is a national holiday. Andrew was the first apostle of Jesus Christ, and is venerated as a saint by the Catholic and Orthodox Churches. He is the patron saint of fishermen and sailors. The name Andrew is of Greek origin (from ανδρεία, andreía, meaning ‘virility, valour, courage’), and it has been found to be very rare among Jewish-Palestinian names at the time of Jesus Christ. According to tradition and his official hagiography, Andrew was born in Bethsaida on the shores of the Lake of the same name in Galilee, and was the brother of Simon Peter. Together with his brother, he was a fisherman by profession, and tradition has it that Jesus himself invited Andrew to become his disciple, and to be for him a ‘fisher of men’ or ‘fisher of souls’ (in Greek ἁλιείς ἀνθρώπων, halieís anthrópon). Andrew was in fact the first to recognise Jesus as the Messiah, having participated in his baptism by John the Baptist on the banks of the Jordan. In the Gospel of John, it is said that Andrew was himself a disciple of John the Baptist. As an apostle of Christ, Andrew saw with his own eyes the multiplication of the loaves and fishes, and together with Peter, James and John heard the prediction of the end of the world from the mouth of Christ. Immediately after the crucifixion of Jesus, according to the testimony of the historian Eusebius of Caesarea, Andrew set off and preached the new faith in Scythia (the region between the Danube and the Don), in Pontus Eusinus, Cappadocia, Galatia and Bithynia.

According to a tradition dating back to the 12th century, Andrew also travelled on the Volga and the Dnieper 1. The historical researcher George Alexandrou has written that St Andrew spent 20 years in the Daco-Roman territories, where he lived in a cave near the village of Ion Corvin in present-day Romania. He then moved to Achaia, the northern region of the Peloponnese, where he was consecrated bishop of Patras. It was in that city that he was martyred on the cross on 30 November around 60 AD. 2. In the earliest Christian apocryphal texts, such as the Acts of Andrew, it is narrated that Andrew was not nailed, but bound on a Latin cross. It was not until around the 10th century that the typical iconography of the crucified saint on a cross known as the Decussate Cross (X-shaped) and commonly known as the ‘Cross of Saint Andrew’ appeared and became common in the 17th century.

Andrew has therefore become a patron saint in many places, such as Scotland, Russia, Prussia, Romania, Ukraine, Greece, Corsica and many Italian cities 3. On 30 November, the day of the celebration of Saint Andrew, in Gesualdo (Avellino) it is traditional to light a bonfire (vampàleria, in dialect) following a ritual that is renewed every year. This tradition started at the beginning of the 19th century, when a large lime tree in what is now Piazza Umberto I was felled to obtain the wood needed to make a statue dedicated to Saint Andrew. With the leftover wood, the faithful then composed a pile that was set on fire as a further sign of veneration, but also, and above all, as an expression of the unity of the people against adversity 4. In Viterbo, but more generally in the capital of Tuscia, there is a special custom: on the feast of the saint, also on 30 November, people exchange gifts of chocolate fish or almond paste. On the evening of the eve of the feast, the children place an empty plate on the window sill, which St Andrew fills with small gifts during the night, together with the inevitable chocolate fish. The St Andrew’s fish has the same function as an Easter egg: melted chocolate is moulded into fish-shaped moulds and a surprise is placed inside. This custom was particularly alive in the ancient district of Pianoscarano, whose parish church is dedicated to St Andrew. In the past, the parish priest used to place chocolate fish in the aquas 5.

In Corsica, the ancient feast of the saint, called ‘Sant’Andria’ in the Corsican language, symbolises the end of autumn and the agricultural harvest, a time when people put aside clothes and food in preparation for winter. The Corsican custom is to dress up and go around the village knocking on doors asking for food and clothes, reciting this prayer: “Apriti! apriti! À Sant’Andria, chì vene da longa via, hà i pedi cunghjilati è hà bisognu di ricaldassi, d’un bon bichjeru di vinu” (Open up! Open up! In Sant’Andrea, if you’ve come a long way, your feet are frozen and you need to warm up with a good glass of wine). Having said that, the landlord opens the door to give people what they want: once “figs and nuts” were given, now also biscuits, chocolates, tangerines and even money. Those who have been generous are thanked, while those who have given nothing are cursed, just as on the night of 31 October, “The Feast of the Dead” 6. In Amalfi, where the saint is patron saint, the feast of St Andrew occurs several times a year. The first is on 28 January, the feast of the relic; the second is on Easter Sunday and Easter Monday; the third is on 7 and 8 May, the transfer of the relics (known as “Sant’Andrea a’quaglia”). The most special ones are on 26 and 27 June, the miracle of St Andrew, and 29 and 30 November, the patron saint’s day. The 27th of June is the anniversary of the miracle of the saint who saved the town of Amalfi from the invasion of the pirate Kair-Ad-Din called Barbarossa in 1544. On this day, the mighty statue of the saint, known by the people of Amalfi as “o’ viecchio” (the old man), is carried in procession through the streets of the town by men dressed in white, belonging to religious congregations. Once on the beach, the fishermen take the statue of the saint and run it back to the cathedral. Once at the cathedral, the fishermen leave Sant’Andrea offers of fresh fish or small iron or wooden fish as a sign of thanks. In the evening, fireworks light up the sky: the pagan festival, hidden under the religious apparatus, finally explodes 7. In Presicce, in the province of Lecce, the saint is celebrated by lighting bonfires along the main streets and squares, over whose flames the so-called ‘triglie di Sant’Andrea’ (St Andrew’s mullets) are roasted 8.

In the north of Spain and in the Basque Country, regions with great maritime traditions, the fishermen’s saint, as well as being the patron saint, is remembered with fairs and festivals featuring the king of Basque cuisine, cod, along with other fish dishes in honour of Saint Andrew 9.

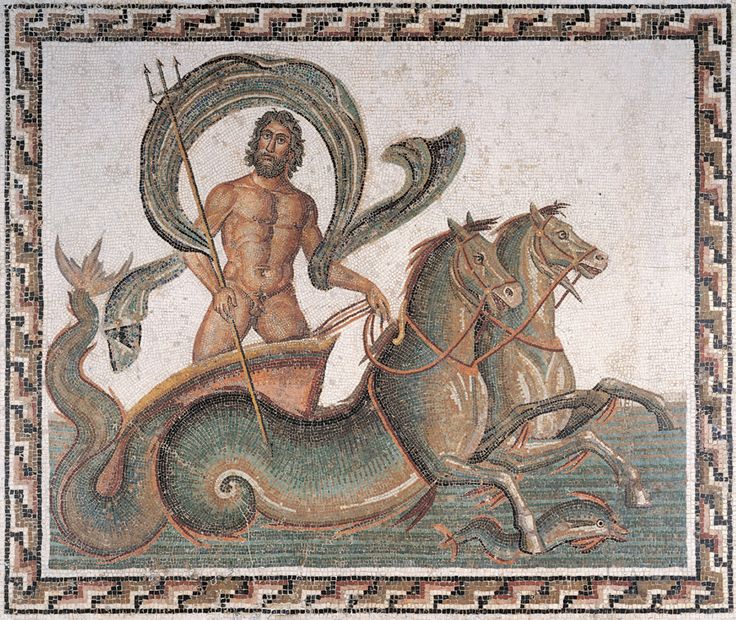

In fact, the specific attributes of the Apostle Andrew are a fish or two fish, stuck in a hook that the saint holds in his hand or laid at his feet, together with a fishing net. The cult of the saint, confirmed by hagiographic narratives and most places of veneration, is linked to islands, sea coasts, waters and aquatic beings. The same characteristics of the saint are found in a much older cult of pre-Christian origin, that of the Greek god Poseidon. The saint is in fact the Christian successor of the Greek god of the seas, a very ancient cult handed down in the new Christian faith. For example, St Andrew and Poseidon are both depicted together with a fish or a dolphin. Poseidon is often seen driving his chariot pulled by seahorses, surrounded by fish, dolphins and other sea creatures. Master of the sea, it is said that he could unleash tidal waves and earthquakes by pounding the seabed with his trident. The trident was the weapon used by tuna fishermen, one of the animals sacred to the god.

Poseidon, just like St Andrew, was worshipped as the main deity in many coastal towns and islands, protecting the inhabitants from calamities and dangers of the sea. In ancient times, fishermen and sailors addressed prayers and rituals to Poseidon to grant them a safe journey and good fishing. Many churches dedicated to St Andrew were built on top of an earlier temple consecrated to the god Poseidon. In the city of Patras, according to studies by the Swiss anthropologist Johann Jakob Bachofen, the Church of St Andrew the Apostle (Agios Andreas) was built on an ancient pagan temple dedicated to Poseidon 10.

Celebrations in honour of Poseidon in the Greek world were held at the beginning of the winter season. According to the inhabitants of Attica, the month of the Winter Solstice was called Ποσιδηϊὼν, ‘Poseideon’, linked to the festivities in honour of the god Poseidon that took place in Athens 11. Also in Rome, the god was celebrated with the Latin name Neptunus, or Neptune. Neptunus was for the ancient Romans the god of fresh water, wells and irrigation. The feast day in honour of Neptune was December 1, the so-called Kalendis Decembribus, confirming the same period and day as the feast day dedicated to St Andrew 12.

The cult of Poseidon, however, appears to be of much older origin, dating back to the Mycenaean period. According to the testimony of some clay tablets in Linear B script from the Minoan period, in the city of Pylos the god was considered the most important of all the gods. Originally, Poseidon was the god of earthquakes (with the epithet Ennosigeus, Ἐνννοσίγαιον, or ‘Shaker of the Earth’) and water (hence his epithet of Υαιήοχος, Gaiéokos, ‘Possessor of the Earth’ understood as the husband of the Earth, or the water that fertilises it). Only in later times did he also become the god of the seas, attesting to the continental origin of the Hellenic people who only settled in Greece around the 15th – 13th centuries BC. Some scholars believe that Poseidon was originally a god-horse, a totemic animal of chthonic and infernal nature. There are frequent connections between Poseidon and the horse, an animal symbol with ancestral roots. His cult was also often linked to horse sacrifice by sailors. This chthonic and infernal aspect of Poseidon remained in the Greek cults of the classical age, but especially in the symbolism of the animals sacred to him 13. Some legends say that dolphins, animals sacred to the god, were in charge of transporting the souls of dead people, leaving their bodies on the land side: it was believed that these animals were responsible for transporting souls. As king of the waters, the dolphin was reputed to be a saviour and psychopomp: it saved shipwrecked people, but also guided souls to the underworld. The Cretans, who worshipped dolphins as gods, imagined that the souls of the dead were to be found at the end of the world, on the islands of the Blessed, and that dolphins would carry them on their backs to the underworld 14. In Indo-European mythology, the horse also has a psychagogue and psychopompa function: it guides souls and accompanies them to their new home 15. The hippocampus, a creature of dual nature, half horse and half fish, pulled Poseidon’s chariot and was part of his court. In some Mediterranean traditions and those of Pontus Eusinus, today’s Black Sea, the hippocampus was considered the helmsman of the boat of the dead to the afterlife. On an ancient coin discovered in Biblos, the hippocampus is depicted in its psychompathic function, carrying on its wings, above the waves, a boat with imprecise shapes and whose rudder is not held by anyone. In a precious stone decorating a Roman ring, found during excavations in the French municipality of Rom (Deux Sèvres), the hippocampus carries a winged child over the sea, perhaps a symbol of the soul 16. The plant sacred to Poseidon is the pine, a tree connected to funeral rites and the realm of the dead, but also a symbol of immortality and salvation 17.

This symbolism is well expressed in the legends linked to the cult of Saint Andrew in Galicia. In the heart of the Sierra de la Capelada, specifically in the municipality of Cedeira, there is a small village overlooking the sea called San Andrés de Teixido, the destination of a very ancient pilgrimage. Like the famous pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela, pilgrims arrive from several paths and places to reach the sanctuary dedicated to the saint, considered the ‘Meca de los Gallegos’, the Mecca of the Galicians. The best known and perhaps the most important popular saying related to the shrine says that: “A san Andrés de Teixido, vais de morto o que non foi de vivo” (You’ll go to San Andres de Tarxido dead if you didn’t go alive). The Galician toponym teixido means ‘place with an abundance of yew trees’. The yew tree is symbolically linked to death and immortality. Here Saint Andrew performs the function of accompanying the souls of the dead, transported by their living relatives to the sacred island.

Although the Chapel of San Andrés was only built around the 12th century, pilgrimage to Teixido is thought to be much older, dating back to the Iron Age, during the Castro culture18. Before the arrival of Christianity, the cult was dedicated to the Galician god Berobreo, the Lord of the sea, the afterlife and death. From the summit of Monta Facho, his great sanctuary, he watches over the Galician islands, resting places for souls on their journey. Berobreo holds the keys to the labyrinths that open the doors between the worlds. At the end of the Saint Andrew’s Path, the earthly mirror of the celestial Milky Way, the god transports souls to his residence in the depths of the waters of the Ocean. This very important cult, which was one of the largest centres of pilgrimage in antiquity, was later absorbed by its Christian successor, St Andrew 19.

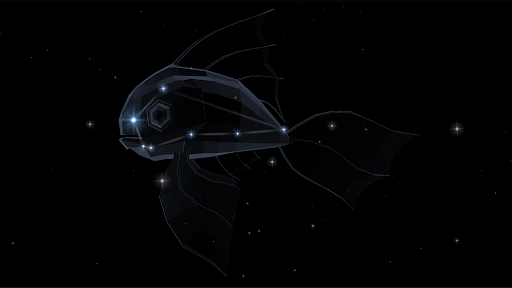

The saint therefore, with his psychopompa nature connected to the cosmic waters, symbolises the passage between autumn past and winter to come. The night between 29 and 30 November is considered a magical night, a timeless space between the material and spiritual worlds where we can ask the spirits and ancestors for a glimpse of the future through divinatory rites 20. On an astrological level, the star connected to St. Andrew, and even earlier to the ancient sea deities, was Fomalhaut. Located in the constellation of the Southern Fish, between 4000 and 2000 BC, it was considered by the ancients to be a royal star and guardian of the Winter Solstice. It is the brightest of the southern stars and one of the four fixed points in the path of the Sun at that time. According to some astrologers, the star has a Jovian-Saturnian nature, carrying the astrological influence of the constellation where it resides. The constellation of the Southern Fish was considered by Eratosthenes to be the Great Celestial Fish, where Fomalhaut, from the Arabic Fom al-ḥūt meaning “mouth of the fish“, is depicted in the act of drinking water flowing from the pitcher of Aquarius21.

Thus, the astral influence coming from the star Fomalhaut, the highest expression of the Southern Fish constellation, manifested itself on earth in various expressions of nature, such as the fish and the dolphin: these totemic animals were later anthropomorphised by the inhabitants of the maritime territories into deities such as Poseidon, Neptune and Berobreo. Finally, with the arrival of Christianity, St Andrew became the descendant of the previous deities of water, death and the afterlife, the divine and hidden expression of the constellation of Pisces.

1 Cattabiani, A. (2013). “Andrea Apostolo”, Santi d’Italia. Milano: Rizzoli.

2 Alexandrou, G. The astonishing missionary journeys of the Apostle Andrew. Orthodox Christianity, https://orthochristian.com/43455.html (last visit 28/11/2020).

3 Andrew the Apostle. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrew_the_Apostle (last visit 28/11/2020).

4 Le Vampalerie di Sant’andrea a Gesualdo, Eventiesagre.it, https://www.eventiesagre.it/Eventi_Feste/21179674_Le+Vampalerie+Di+Sant+andrea+A+Gesualdo.html (last visit 28/11/2020).

5 Il pesce di Sant’Andrea, un’antica tradizione viterbese, Movemagazine, https://www.movemagazine.it/pesce-sant-andrea-tradizione-viterbese/ (last visit 21/11/2020).

6 Sant’Andria, Ecole des Cannes, http://web.ac-corse.fr/ia2a/cannes/m/SANT-ANDRIA_a31.html (last visit 21/11/2020).

7 Festa di Sant’Andrea Apostolo, Amalfi.gov.it, https://www.amalfi.gov.it/events/festa-di-sant-andrea-amalfi/ (last visit 21/11/2020).

8 La tradizione delle triglie di Sant’Andrea a Presicce, Puglia.info, http://www.puglia.info/blog/index.php/la-tradizione-delle-triglie-di-santandrea-a-presicce-7137.html (last visit 21/11/2020).

9 Sant’Andrea dei pesci, Taccuini Gastrosofici.it, https://www.taccuinigastrosofici.it/ita/news/medioevale/usi-costumi/print/Santo-Andrea-dei-pesci.html (last visit 21/11/2020).

10 Ibidem.

11 Poseidone. Wikipedia, L’enciclopedia libera, https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poseidone (last visit 21/11/2020).

12 Festività della Roma Antica – Festa di Neptunus (VIII secolo a.C. – IV secolo d.C.). Mediterranian Fantasy, http://medfantasy.altervista.org/festivita-della-roma-antica-festa-di-neptunus-viii-secolo-a-c-iv-secolo-d-c/ (last visit 21/11/2020).

13 Poseidone. Wikipedia, L’enciclopedia libera, https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poseidone (last visit 21/11/2020).

14 Il Delfino: mitologia e simbolismo. Omega Outpost, https://theomegaoutpost.wordpress.com/2015/11/04/il-delfino-mitologia-e-simbolismo/#:~:text=Le%20prime%20storie%20che%20riguardano,guidava%20le%20anime%20nell’oltretomba. (last visit 21/11/2020).

15 Il cavallo: simbolo, significato, leggende, miti, spirito guida. Caverna Cosmica, https://www.cavernacosmica.com/il-cavallo-simbolo-significato-leggende-miti-spirito-guida/ (last visit 21/11/2020).

16 Charbonneau-Lassay, A. L. (2006). Le Bestiaire du Christ. Parigi: Éditions Albin Michel, pp. 1439-1441.

17 Pino. Leggende e usi magici delle erbe. Caverna Cosmica, https://www.cavernacosmica.com/significato-pino/ (last visit 21/11/2020).

18 San Andrés de Teixido. Wikipedia, La enciclopedia libre, https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/San_Andr%C3%A9s_de_Teixido (last visit 21/11/2020).

19 Berobreo. Galipedia, a Wikipedia en galego, https://gl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berobreo (last visit 21/11/2020).

20 La notte del lupo che porta l’inverno, Terre Celtiche Blog, https://terreceltiche.altervista.org/la-notte-del-lupo-porta-linverno/ (last visit 21/11/2020).

21 Cattabiani, A. (1998). Planetario: simboli, miti e misteri di astri, pianeti e costellazioni. Milano: CDE, pp. 238 – 242.