Saint Columbanus and the symbolism of the dove

Saint Columbanus and the symbolism of the dove

by Hasan Andrea Abou Saida

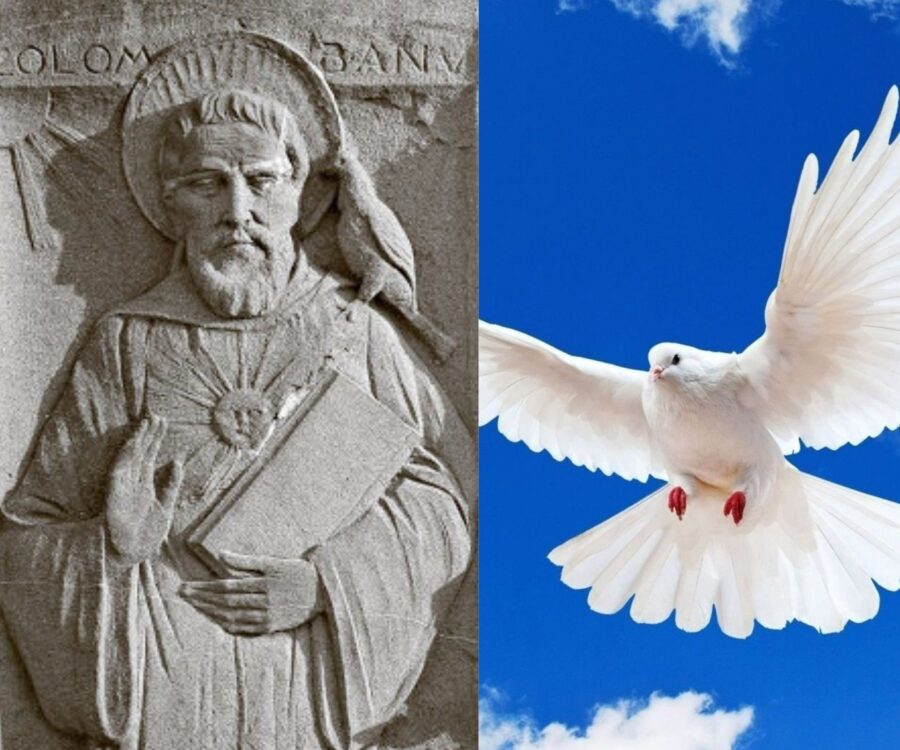

Saint Columbanus of Bobbio is recognised as one of the masters of Western monasticism. He founded numerous monasteries and churches throughout Europe, contributing to the spread of Irish monasticism in particular. According to stories, Columbanus was born in a village in Leinster around 534 AD. According to one legend, when his mother had just conceived him, she suddenly saw a glittering sun emerge from her womb one night. Asked for guidance from those who had the authority to interpret a supernatural sign, he learned that “she had in her womb a man of great qualities who would accomplish things useful for her salvation and opportune for the good of her neighbour”. The young Columbanus was taught by a fili master (from *widlu-, “to see”), who belonged to a class of poets and sages with the functions of magicians, legislators, judges, counsellors of authority and poets. From this master, Columbanus was initiated into the art of writing, reading, mnemonics, the seven liberal arts and the Holy Scriptures. The Celtic Church of Ireland, in fact, supplemented the teachings and many uses of the string class. At the age of fifteen, Columbanus left home to become a monk. He moved to the monastery on Cleenish Island in Lough Erne, and later moved to Bangor Abbey in Northern Ireland. After many years of study, prayer and work, Columbanus decided to take up missionary life and leave Ireland. According to Irish monastic tradition, it was from Bangor that the saint began his pilgrimage to evangelise and found new Christian religious centres in Europe. At the age of fifty, he left with twelve companions for France, where he founded numerous monasteries, including those of Annegray, Fontaine and Luxeuil, and later that of Bobbio in Italy in 614 AD. 1.

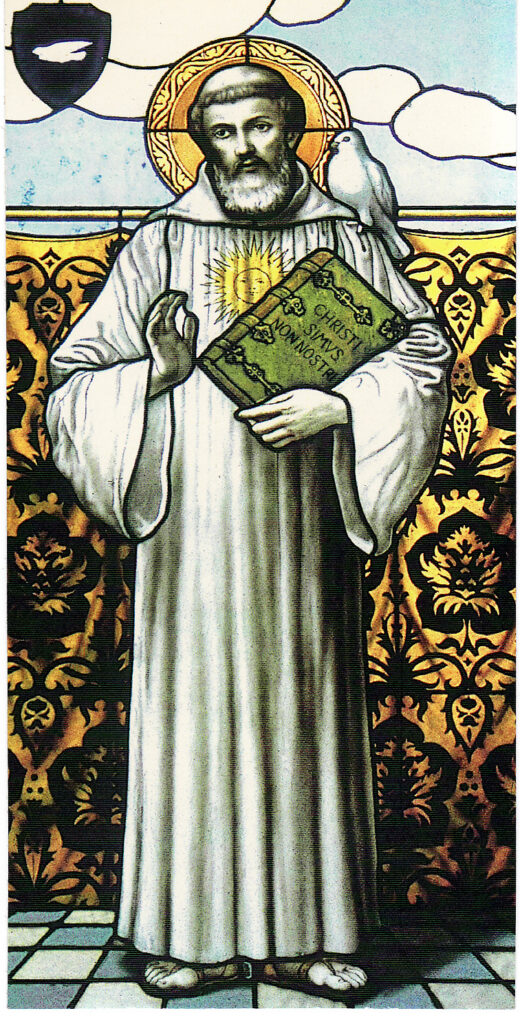

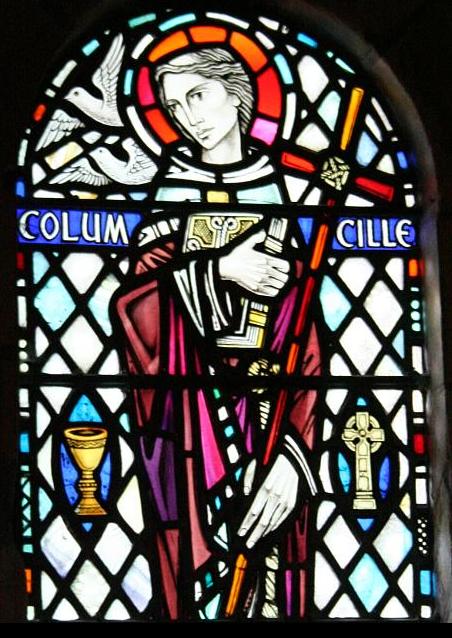

Shortly before the departure of Saint Columbanus and his twelve companions, another missionary saint, Columba of Iona, who introduced Christianity to much of Scotland, died. Columba of Iona, is one of the most important Irish monastic figures and is venerated as one of the patron saints of Ireland, along with Saint Patrick and Saint Brigid of Ireland. According to the chronicles, Colum Cille was born in Ireland to Fedhlimidh and Eithne of the Uí Néill clan of Gartan. Of royal lineage, as the great-grandson of Niall Noigíallach (‘Niall of the Nine Hostages’), a fifth-century Irish king, he received an education very similar to that of Saint Columba. He went to Leinster to the school of an old bard, Master Gemman, where he learned the art of music, verse writing, grammar, history and Irish literature. After finishing his studies with the bard, Columba entered the monastery of Clonard, ruled at that time by Saint Finnian, known for his holiness and knowledge. Here he learned the traditions of the Welsh church, as Finnian had studied at the schools of Saint David of Wales. His missionary work began in 563 AD with the foundation of a monastery on the island of Iona, off the west coast of Scotland, one of the most important religious centres in Western Europe. Columba arrived there with twelve companions, just as Saint Columba did later on 2. As can be seen, the two saints bear the symbol of the dove, both in their names and in their deeds: Columbanus, from the Gaelic Colum Bán, means ‘white dove’, while Columba of Iona, from the Irish Gaelic Colum Cille, means ‘dove of the Church’. In the Christian tradition, the dove represents purity and appears as a heavenly messenger, the breath of the Holy Spirit. The spread of Christianity by the two saints was a cosmic message of spiritual renewal, a proclamation of change through the spirit of the dove.

Thanks to the excellent skills of the illuminating monks, the natural symbolism of Celtic art was conveyed, and much of the Celtic tradition was concealed under the symbolism of the new Christian religion. The white cassock and a particular type of monk’s tonsure, called Saint John’s or Simon Mago’s, were both a legacy of the ancient customs of the Druids (the Irish term Mael is used to indicate a bald person but also a sage). The tonsure of St John, also known as the “Celtic tonsure” was adopted in Ireland, Britain, Asturias and Galicia and in general by all Christian monks in or originating from Celtic countries, and was a characteristic expression of Celtic Christianity in Europe, but was condemned by the Council of Toledo in 633 AD. 3. The Celtic Church in fact, strongly characterised by ancient Irish traditions and myths, had its own autonomy and its own roots, sometimes diverging from the Roman Church. Despite these divergences, however, the Celtic Church was never a heresy and there was no schism, since Celtic Christianity or Christian Druidism was rather a type of organisation that the new religion took in countries with a strong Celtic presence 4.

Many of the symbols found in Christianity, such as the dove, have much older roots, originating in Celtic cults, and even earlier in prehistoric stellar cults. The dove, often assimilated to the raven, was associated with healing and oracular powers. At the sanctuary of Dodona in Greece, for example, originally dedicated to the Mother Goddess, and later shared between the gods Zeus and Dione (the female form of Zeus), the priestesses were called peleiades (‘doves’) and the oracle interpreted the flight of the doves and questioned Zeus’ sacred oak tree for answers and to communicate with the Otherworld 5. Sccording to an ancient legend, the founding place of the city of Pavia, formerly called Ticinum, was chosen on the divine indication of a dove. The story goes that the Druid elders, belonging to a nomadic Celtic tribe that had settled in the area, decided to entrust the gods with the foundation rite of the settlement, and to do so they chose the chief’s daughter, a young virgin. The young Celtic girl, after having purified herself with a lustral bath, with her head wrapped in oak leaves, intertwined with willow saplings, privets, daffodils and sacred herbs, took a white dove in her hands and, after having “offered” it to the four sides of the horizon, she raised the bird high on her head and, joining her invocation to those of the whole tribe, she opened her hands and let it fly. The dove flew to the east and its magical flight was followed with great trepidation by the tribe who saw it stop on a branch of a giant oak tree where it built its nest. On that spot, they built their village, where the Romans would later found the city of Ticinum 6.

The dove is therefore originally a female symbol, linked to divination, spring rites, fertility and rebirth. In Irish Celtic mythology, the dove is one of the animals sacred to the goddess Brighid, the Great Goddess par excellence, associated with spring and fertility. Brighid is the goddess of fire, the sun, the moon, animal breeding, blacksmithing, fertility and birth, family, hearth, spinning and weaving, music and poetry, war, medicine and divination 7. In one legend, it is said that Saint Brigid of Ireland (the Christianisation of the Celtic goddess Brighid and, according to legend, also instructed in her youth by the Druids), saw a white dove one day that led her to a deserted place, where she assisted as midwife at the birth of the baby Jesus. In that place there were cows that, burning with thirst, could not produce milk to suckle the newborn baby. Brigid sang them the “poems of paradise” and milk began to flow copiously for the Holy Child 8. Because of these attributes, the saint is associated with the Celtic goddess Brighid and the totemic animals associated with her, namely the cow and the dove, both linked to the Celtic Otherworld.

In the Celtic annual cycle, the festival dedicated to fertility, rebirth and the beginning of Spring-Summer is called Beltane and is traditionally celebrated on 1 May. The word Beltane or Beltine, which literally means “fire of Bel” (it is still used to designate the month of May in modern Irish) is linked to the god Belenos, the supreme god of light and sacred fire, and to his wife, the goddess Belisama, goddess of Fire and Waters, which is not by chance one of the epithets of the Irish goddess Brighid. On the day of Beltane, the fertility rites of the earth were celebrated, in which the Mother Goddess united with the Solar Goddess so that the fruits of the earth could be generated 9. This day marked the beginning of the fine season and the bright second half of the Celtic year, during which a group of stars very important to the Celts, the Pleiades, rose. Called in ancient times “the Seven Sisters”, they are the brightest stars in the constellation Taurus and marked the beginning of the new agricultural year and the mating season for animals. According to a Greek legend, before becoming stars, the Pleiades were originally the seven nymph companions of Artemis. One day they met the hunter Orion and became his prey. To protect them and escape the hunter’s pursuit, Zeus turned them into doves and released them into the sky. The name of the constellation in fact derives from the Greek péleiades, which means “doves” 10.

Of all the Pleiades, the most beautiful was Maia, daughter of Atlas and Pleione or Sterope. Maia was a wood nymph who lived on Mount Cillene in Arcadia and was the lover of Zeus, with whom she gave birth to the god Hermes. Originally, the nymph was a great female divinity, worshipped in archaic times 11. The goddess Maia, an ancient goddess of fertility and the awakening of Nature, was also worshipped in Rome. The first day of May and the month itself (from the Latin Maius, meaning “May”) were dedicated to her 12. In fact, the name Maia (from the Greek Μαῖα) means “mother”, “nurse”, and sometimes “grandmother”, carrying with it the highest aspects of the sacred feminine 13. According to the Polish scholar Andrzej Niemojewski, the star Maia would represent the Virgin Mary in the Christian tradition (variant of the name Maia – Maja). In early Christianity, the mother of Jesus was a dove, the animal symbol of the Virgin Mary. The month of May is traditionally dedicated to Marian cults 14.

In conclusion, the dove, since the remotest antiquity, has been a symbol of the sacred feminine connected to the influence of the Pleiades, handed down over the centuries through its divine manifestations, and still present today in Christian cults, embodied in the saints who bear its name.

1 Cattabiani, A. (2013). “Colombano di Bobbio”, Santi d’Italia. Milano: Rizzoli.

2 Columba di Iona. Wikipedia, L’enciclopedia libera, https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Columba_di_Iona (last visit 21/11/2020).

3 Taraglio, R. (2005). Il vischio e la quercia: la spiritualità celtica nell’Europa druidica (Nuova). Torino: L’età dell’acquario, pp. 394 – 395.

4 Ivi, p. 393.

5 Dodona. Wikipedia, L’enciclopedia libera, https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dodona (last visit 21/11/2020).

6 Un fiume, una fanciulla, una colomba. Ticinum Papia, http://www.ticinum-papia.it/colomba.htm (last visit 21/11/2020).

7 Taraglio, R. (2005). Il vischio e la quercia: la spiritualità celtica nell’Europa druidica (Nuova). Torino: L’età dell’acquario, p. 188.

8 Santa Brigida di Irlanda. Spazio Sacro, http://spaziosacroaltaredibrigida.blogspot.com/2013/01/brigida-la-santa.html (ultima visita 21/11/2020).

9 Taraglio, R. (2005). Il vischio e la quercia: la spiritualità celtica nell’Europa druidica (Nuova). Torino: L’età dell’acquario, p. 370 – 371.

10 Pleiadi (mitologia). Sapere.it, https://www.sapere.it/enciclopedia/Pl%C3%A8iadi+%28mitologia%29.html (last visit 21/11/2020).

11 Maia (pleiade). Wikipedia, L’enciclopedia libera, https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maia_(pleiade) (last visit 21/11/2020).

12 Maia (divinità). Wikipedia, L’enciclopedia libera, https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maia_(divinit%C3%A0) (last visit 21/11/2020).

13 Maia. Treccani Enciclopedia online, https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/maia/#:~:text=%C3%A8%20amata%20da%20Zeus%20in,mitologica%20di%20alta%20dignit%C3%A0%20femminile. (last visit 21/11/2020).

14 Drews, A. (1912). The Witnesses to the Historicity of Jesus. Chicago: Watts, p. 214.

Bibliography

Arecchi, A. (2000). Pavia : leggende e magia dai Celti ai Visconti. Pavia: Liutprand.

Cattabiani, A. (2013). Santi d’Italia. Milano: Rizzoli.

Drews, A. (1912). The Witnesses to the Historicity of Jesus. Chicago: Watts.