The totemic origins of the cult of Saint Homobonus

The totemic origins of the cult of Saint Homobonus

by Hasan Andrea Abou Saida

Saint Homobonus, besides being the patron saint and symbol of Cremona, is the patron saint of merchants, textile workers and tailors. According to his hagiography, Omobono Tucenghi was a tailor and wealthy textile merchant who lived between 1150 and 1197. Around the age of fifty, he decided to devote himself entirely to charity work and abandon his businesses, and was hindered by his wife and children. Throughout his life, he dedicated himself to good works and distributed large amounts of alms: according to legend, his purse was always full of coins and was never emptied by divine Providence. Because of these qualities, he became a popular and beloved citizen, legendary for his moral standing and goodness of heart. He was the first non-noble layman to be canonised in the Middle Ages, and was proclaimed a saint just two years after his death by Pope Innocent III in 1199. One of the most famous miracles attributed to the saint is that of having stopped, by making signs of the cross with his stick, a terrible flood of the River Po that had already invaded a large part of Cremona and threatened to engulf the whole town 1.

The cult of Saint Homobonus, however, in its symbolic essence has much more ancient roots, taking on the role of a city ‘totem’, a symbol characterising the soul of Cremona. This particular city archetype is found expressed in the cult of the hero Hercules, the legendary founder of the city of Cremona. The characteristics and essence of a city’s totem, in fact, are handed down in popular tradition in the form of stories, myths, legends and even fairy tales. According to the myth, the demigod Hercules, on his return from Iberia, after retrieving the Pomi of the Hesperides, stopped to rest on the banks of the river Po. At that time, the area was infested with thieves of gigantic stature who plundered the small villages in the vicinity. When they heard that the famous hero was in the area, the older inhabitants came to him and asked him to help them get rid of the robbers. Hercules did not hesitate long and decided to face the robbers alone. In a very short time he defeated and killed them, finally freeing the territory from that terrible evil, but before leaving he decided that those people needed a safe place to protect themselves in case new robbers arrived. So he founded a fortified city and named it after his mother Alcmena, which in time became Cremona 2. One of the names of the city of Cremona is in fact “Erculea”, recalling our hero.

It is a common belief among scholars that the religiosity of the people, a “popular Christianity”, continued to be influenced by earlier pagan beliefs, and that they in fact unconsciously found several similarities between the figure of Omobono Tucenghi and Hercules: both are heroes and saviours of the city. Moreover, Hercules is the protector of trade and merchants, just like Saint Homobonus. Finally, both figures are depicted with solar connotations and symbols, such as the golden apples of the Hesperides for Hercules and the bag full of gold for Saint Homobonus. There is a statue on the Torrazzo next to Cremona Cathedral that is said to represent the hero Hercules, with an appearance that does not exactly correspond to his classical but medieval iconography. According to the testimony of the Cremonese historian Antonio Campi, the statue was discovered in 1417 and placed on the façade of the Cathedral, between the sculptures of a lion and a bull, animals present in two episodes of the hero’s twelve labours 3.

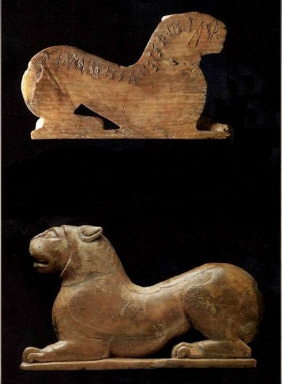

Through a comparison of the cults of Saint Homobonus in Italy and archaeological investigations in the churches dedicated to him, the inheritance of the cult from the hero to the saint can be confirmed. In the sacred area of Sant’Omobono in Rome, discovered in 1937 near the church of Sant’Omobono, they found the remains of two terracotta statues belonging to the former archaic Etruscan temple from the 6th century BC. One statue depicts the god Hercules, with a lion skin tied over his torso, while the other represents a female figure with a helmet with a paraguance and a high crest, possibly Minerva, or Bellona or armed Fortune 4.

Moreover, the presence of a Hercules cult in the Etruscan temple is confirmed by the discovery of an ivory hospitalis tessera in the shape of a lion (Hercules’ symbolic animal), carved on one side only, with an Etruscan inscription on it: “Araz Silqetenas Spurianas”, a tribute dedicated to the deity in the sanctuary 5.

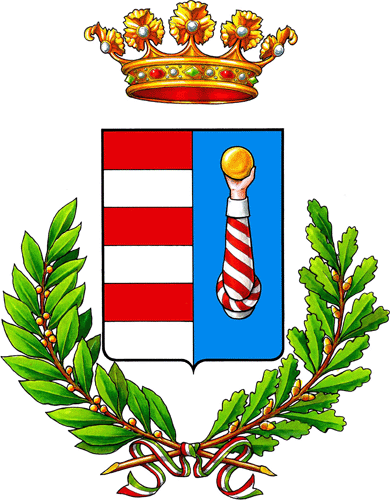

Another warrior hero present in Cremona with the same solar warrior attributes is undoubtedly Giovanni Baldesio, known as Zanén de la Bàla, who lived between 1052 and 1128. The Cremonese hero, whose legend is well rooted in the city, is venerated for having freed the city of Cremona from the domination of the Holy Roman Empire. It is said that Cremona at that time had to pay the emperor a tax consisting of a five-kilo ball of gold every year. In order to free the city from this tax, the people of Cremona delegated Zanén de la Bàla to challenge Henry IV of Franconia, son of Henry III, in combat and in case of victory the city would no longer pay the tax. The Cremonese hero won, and his story is still remembered today with Cremona’s coat of arms, which features an arm with a golden ball and the words fortitudo mea in brachio, or “my strength is in my arm” 6.

This cult of heroes and gods has its own totems (animals, plants, etc.), true protective spirits. The qualities of the primary totem of each city can be traced back to the most important local archaic deities and heroes. For Cremona, the primary totem is the lion, a solar animal symbol of sovereignty, power, courage and strength. In Roman times, there were as many as three temples dedicated to Hercules in Cremona and there were numerous dedicatory epigraphs in the area, confirming the importance of the cult at local level. In fact, the hero Hercules is always depicted with the skin of the Nemean lion as his cloak, a totemic attribute of kings and heroes, and from which he draws divine strength by turning into a lion.

The same totemic qualities can be found in the Celtic counterpart of Hercules, the god Ogmios. The god is depicted as an old man with a bald forehead, caned, with wrinkled, burnt and black skin, but with all the attributes of the Greek/Roman hero, such as the leontes, quiver, club in the right hand and bow in the left hand 7.

According to a Cremonese legend, confirming the importance of this totem, a lion was buried in the foundations of the Torrazzo. Another story, reported by the Cremonese notary Domenico Bordigallo in his Chronica seu historia of 1527, tells how Cremona remained uninhabited for a long time after the Lombard king Agilulfo destroyed it. One day, a Gaulish prince and his army camped near the ruins of the city. A lion came limping up to him and showed him its paw, which was bleeding from a thorn. The prince, not at all frightened, treated the lion’s paw, which then disappeared, and returned with a gift of a roe deer. The next morning the prince set off again, and the lion followed him on his way to Rome. After several journeys and undertakings, however, the lion passed away. The prince then decided to return to Cremona to rebuild it and as a first step he placed the lion’s bones in the foundations of the Torrazzo. In memory of this gesture, a metal lion with raised paw was placed on top of the Torrazzo, in memory of the lion that raised its wounded paw towards the prince. According to Domenico Bordigallo’s chronicles, a large bell was made from the metal of the statue a few centuries later 8.

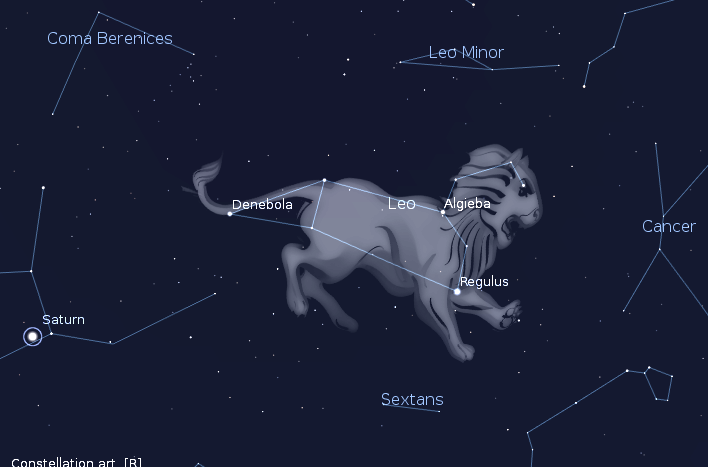

Studies by various authors from the geographical astrological tradition (i.e. the branch of astrology that identifies connections between places on Earth and astrological signs on the basis of their degree of energetic affinity) further confirm the link between Cremona and the lion, as Cremona’s birth sign is in fact that of Leo 9.

In conclusion, it can be said that the astral influences deriving from the Leo constellation were reflected most strongly in the Cremonese territory, creating a deep spiritual connection with the zodiacal function of Leo, thus manifesting the Leo qualities and characteristics in divine cults throughout the ages.

1 Cattabiani, A. (2013). Santi d’Italia. Milano: Rizzoli, p. 750.

2 Campi, A. (1585). Cremona fedelissima città, et nobilissima colonia de Romani,…. Cremona: Hippolito Tromba & Hercoliano Bartoli, p. 1.

3 Ibid.

4 Area Sacra Sant’Omobono. Romano Impero.com: https://www.romanoimpero.com/2010/03/area-sacra-santomobono.html (last visit 12/11/2020).

5 Tessera hospitalis. Wikipedia, L’enciclopedia libera, https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tessera_hospitalis (last visit 12/11/2020).

6 Giovanni Baldesio. Wikipedia, L’enciclopedia libera, https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giovanni_Baldesio (last visit 12/11/2020).

7 Ogmios. Treccani.it : https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/ogmios_%28Enciclopedia-dell%27-Arte-Antica%29/ (last visit 12/11/2020).

8 Beneggi, A. (2011). La “Cronicha” di Domenico Bordigallo. Unversità degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, http://www.fedoa.unina.it/8793/1/BENEGGI.pdf (last visit 12/11/2020).

9 Città, Nazioni e Segni zodiacali. Renzobaldini.it: http://www.renzobaldini.it/citta-nazioni-e-segni-zodiacali/ (last visit 12/11/2020).